Recent OECD, IEA, NEA, ITF Report Identifies Current Policies That Are Not in Line With Creating a Low-Carbon Economy

The ‘Aligning Policies for a Low-Carbon Economy’ report, published the OECD, IEA, NEA & ITF focuses on contradictory public policies, such as those that encourage investment in fossil fuels and work against global goals on climate change. It examines the policy domains of investment, taxation, innovation and skills, trade and adaptation, as well as sectors greatly impacting the climate such as electricity, urban mobility and rural land use. In the report Sustainable Urban Mobility measures are presented as consistent to the stabilization of the increase of global warming to 2-degrees.

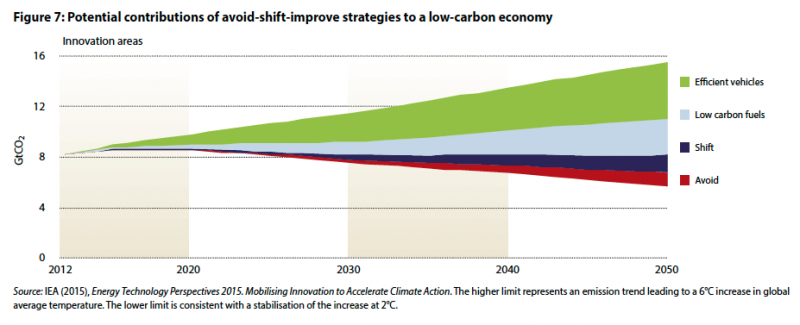

Reliance on fossil fuel-based transport systems has a very high local and global environmental price tag. The transport sector produces roughly 23% of global CO2 emissions development needs and is the fastest-growing source globally. Without further policy action, CO2 emissions from transport could double by 2050. Reducing emissions from transport could also result in cleaner air and less congestion, but this will not happen without proactive and joined-up policy action to:

● Avoid travel and reduce the demand for total motorised transport activity.

● Promote the shift to low-emission transport modes.

● Improve the carbon and energy efficiency of fuels and vehicle technologies

With these three points a scenario is presented by the OECD, IEA, NEA & ITF report that shows Avoid-Shift-Improve measures up to 2050 are consistent in stabilizing global warming to 2 degrees. This can be seen in the emission reduction potentials in the graph presented below, produced by the reports authors.

The Avoid–Shift-Improve measures should be embedded in a strategy for urban development that makes more efficient use of space and takes into account environmental costs, wellbeing and economic development needs. This would mean refocusing urban transport policies on access rather than mobility itself, providing safe infrastructure for walking and cycling, shifting to mass transport modes where demand is concentrated, developing cities along mass transit corridors, and improving fuel and vehicle efficiency.

Many cities in OECD countries are already designed around the private car. They will need very low – or even zero – emission fuels and vehicles, more efficient public transport systems, land-use planning that reduces the need for personal vehicles and alternatives to transport demand (such as teleworking) if they are to reduce CO2 emissions significantly. In cities in developing and emerging economies, where much of the infrastructure is yet to be built, urban expansion needs to be managed in a way that limits the demand for energy-intensive mobility while promoting safe, affordable, accessible and sustainable transport systems for all. Sub-national governments are critical decision makers for urban transport planning, but co-ordination, general framework and capacity are generally barriers to subnational governments making greater efforts toward climate action. The way forward is reasonably clear, but several policy misalignments need to be corrected to allow urban mobility to develop while reducing its carbon footprint.

Download the full report here