12 September 2022 In Blog Post, Informal Transport, News

Exploring the role of informal transport in Africa’s transition towards inclusive, sustainable and decarbonised transport

Rising fuel prices have severely impacted Nairobi’s informal transport fleet. In an effort to find relief, some matatu drivers have been filling up their tanks with cheap but adulterated fuel. The dirty mix destroys the injector nozzles and increases air pollution, impacting the respiratory health of passengers, transport workers, and people who live near major road networks. In the past, there have been just a few, isolated actions to address climate change in Kenya’s informal transport sector. Recently, the future arrived in Nairobi, the country’s capital, when two electric minibuses joined the city’s matatu fleet (see photo below). As more of these EVs enter service, we will expect to see more opportunities to improve informal transport while addressing climate change. But beyond a shift in technology and vehicle electrification, decarbonising the informal transport sector in Kenya will require a true understanding of the sector, its limitations, and the needs not only of workers and operators, but of other actors involved in the transport ecosystem.

Kenya has a privatized road passenger transport service that is formally regulated but operates informally. Informal transport in Kenya can be traced back to the 1950s, when the sector grew rapidly after the country’s independence and the subsequent migration of more people from rural areas to the growing cities. The growing population and the geographic spread of the city increased the demand for transportation. Entrepreneurs cobbled and improvised from existing vehicles—innovating them into viable mobility solutions. They ran routes and charged a thirty cents fare, and thus the iconic matatu was born. (“Matatu” is Kikuyu for “three.”)

Despite the government’s failure to provide efficient publicly owned transportation, the existing industry serves the public, but it does not qualify to be a public transport service. Service is stifled by policies, laws and regulations that do not support the industry’s growth. Regulators have long struggled to deliver safety and improve informal transport services. However, relying more on punitive measures, regulators threaten and suspend operating licenses of companies and cooperatives for non-compliance. But enforcement is sparse, and punishment shows little success in driving reforms.

While scholars and academics have written a lot about Kenya’s matatus, no viable solutions have emerged to ease the persistent challenges of the current state of informal transportation. Perhaps the solutions must come from the industry itself, from the inherent innovation of the matatus. These services have been with us for decades, and as our cities grow ever more, our matatus are now joined by three-wheeler tuk-tuks and two-wheeler boda-bodas. They are not going away. We cannot regulate them away. We must shift the narrative. Rather than banning them from operating in our cities, we must focus on how we can improve and integrate informal transportation with all other means of transportation (proposed, current and yet to be).

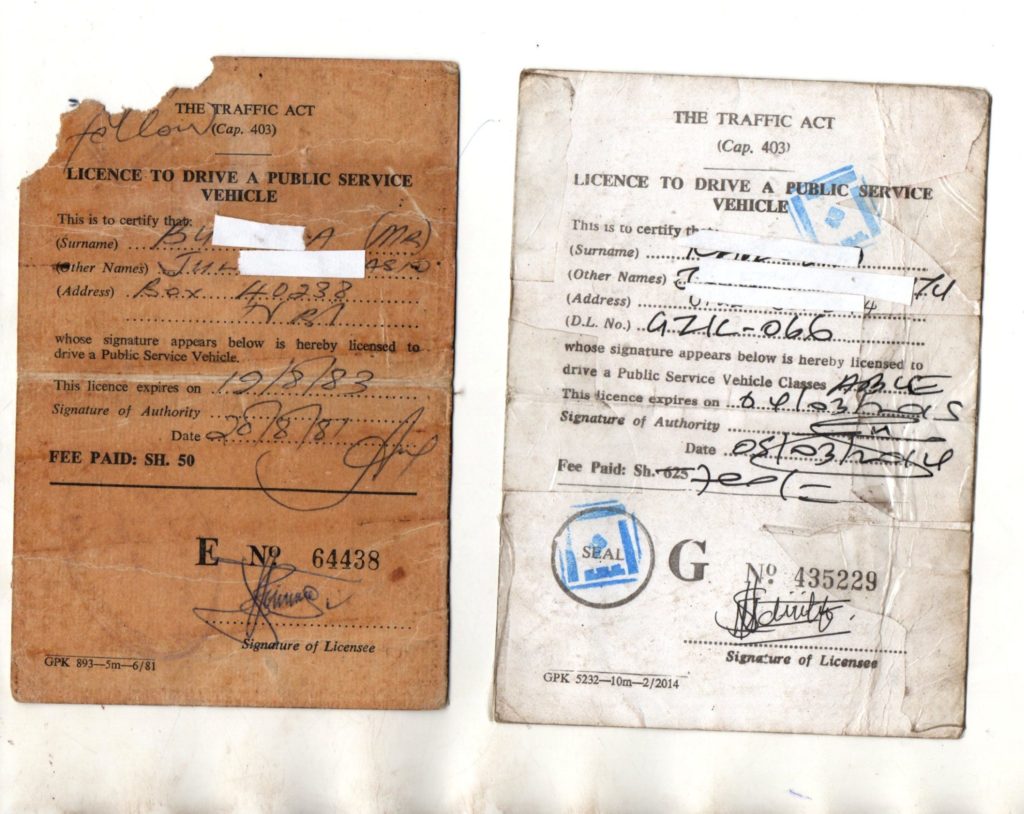

As mentioned beforehand, the informal public service vehicle (PSV) industry and its workforce is highly regulated by the National Transport and Safety Authority (NTSA), under Kenya’s Ministry of Transport, Infrastructure, Housing, Urban Development and Public Works. NTSA requires licenses for drivers and conductors (see photo below). Further, Kenya has devolved the management of public transportation to local governments. It is unclear therefore if the central (national) government sets the policies for informal transportation, or if it’s the 47 county governments who do so, and whether they have the capacity to do so, thus generating governance and regulatory issues.

The lack of clarity in governance and regulation benefits no one. For too long, we’ve tolerated how endemic corruption extracts from the earnings of informal transport workers. This has compounded the dysfunctions in the sector, the results being serious and fatal crashes. Thousands of lives have been lost, with many more disabled from serious injuries. No government official has ever taken responsibility for these crashes. Nothing is said about the post-crash life of the victims. Going forward, there should be zero-tolerance of these unnecessary deaths and injuries. But as above, the long-term solutions won’t come from threats of punishment but from investing in the training of workers and operators on road safety so they are not left behind. One good example is the Transport Education Training Authority of South Africa and there are many emerging efforts like it.

Another limitation for informal transport in Kenya is that the public, and workers in the informal world of road transport lack access to basic rights in public transport and this again limits growth of the sector. Workers and passengers by extension need to enjoy eco-friendly buses, safe environmentally working stations that will free them from fatigue, dust, floods, or hazardous smoke emitted from vehicles (see photo below). Beyond the drivers and conductors, the informal transport sector has generated a multitude of other jobs and businesses. Mechanics, artisans, technicians, painters, clerks, graphic designers, tire menders, and many other livelihoods service informal transportation and are fully dependent on the industry. Therefore, when thinking about how to incorporate the informal transportation sector in climate action, taking this into consideration is essential and calls for an integrated approach focusing on a just transition from informality.

Another place we can start is by restructuring the ownership of informal transportation. With such tight profit margins, the current model of private, individual ownership translates to less motor vehicle maintenance. We should create adequately resourced cooperatives and publicly-owned local companies and assign ownership to these organizations. The public and shared ownership models would cater better to the welfare of workers and passengers.

What if matatu workers started earning a living wage? What if we created better livelihoods for workers while providing passengers more affordable (and fairer and predictable) fares and safer rides? What if profits were reinvested to improve public transport infrastructure and services?

Decarbonising the transportation sector presents a new opportunity to bring informal transportation workers to the table. They should be listened to, and their ideas incorporated to improve public transport and make cities liveable and habitable. Workers and passenger rights in informal transport should be clearly spelt out and communicated in a language best understood.

The informal transport sector has been left behind in times of crises, calamities and pandemics. They should not be left behind this time around, but instead allowed to lead in road safety campaigns, climate action and decarbonisation. Beyond compliance, allowing the sector to lead will encourage accountability, responsibility and ownership.

Joseph Ndiritu

Joseph Ndiritu has worked in the informal transport sector in Kenya, and being an immediate former matatu driver and a fleet manager, he is now organizing labour in the industry through a trade union he championed for its registration, the Public Transport Operators Union (PUTON), of which he is the current National Chairman.

Joseph Ndiritu

Joseph Ndiritu has worked in the informal transport sector in Kenya, and being an immediate former matatu driver and a fleet manager, he is now organizing labour in the industry through a trade union he championed for its registration, the Public Transport Operators Union (PUTON), of which he is the current National Chairman.