Over the past year, the electrification of transport has captured the political zeitgeist. Governments across the world are announcing ambitious e-mobility targets for the transport sector, investing heavily in new e-bus public transport schemes and mandating car manufacturers to increase electric vehicle sales. There has been no shortage of excitement in the private sector either, with companies racing to build new electric vehicle and battery manufacturing plants, such as Britishvolt’s recent announcement that it will be building the UK’s first battery gigafactory in Blyth.

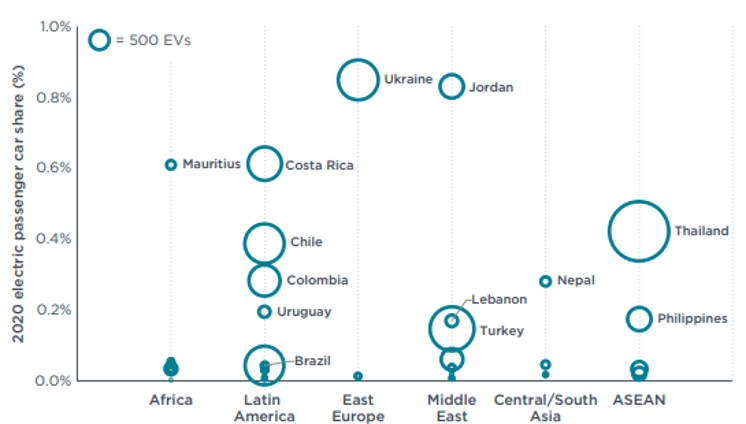

In emerging economies like India, Indonesia, Rwanda, South Africa or in many countries in Latin America, the appeal of transport electrification is also gaining ground. At the end of 2021, it was estimated that $25 million in funding had been secured by Sub-Saharan Africa’s EV start-up ecosystem. It must be noted however that the adoption of electric vehicles in Africa has been more sluggish than other regions, where the share of EV cars across the vehicle market registered less than 0.1% of sales.

Amid the goldrush of VC and development funding pouring into a budding ecosystem of electric two and three-wheeler startups and e-bus initiatives, it is easy to lose sight of the reality of how transport networks are operated in emerging-market cities.

Informal transport continues to make up the lion’s share of lower-income countries’ urban transport networks. In the region of Gauteng, South Africa for example, WhereIsMyTransport found that 82% of the public transport network is made up of minibus taxi routes. In short, informal transport plays a significant role in meeting people’s travel needs, accounting for the majority of public transport provision in emerging-market cities.

Gauteng’s formal and minibus taxi route network

Legend: minibus taxi routes (orange) - formal routes (grey)

The ways these minibus taxis and other informal modes operate are a far-cry away from the spick and span operating models of Singapore’s Mass Rapid Transit, London’s TfL or Berlin’s U-Bahn agencies. Instead, informal transport systems tend to have semi-fixed routes, on-demand stops, discretionary fares decided by the driver, and are generally unregulated. More importantly, they are run by hundreds to thousands of drivers and family businesses, each operating independently from one another.

If public transport networks in developing cities are to be effectively decarbonised, the question of informal transport electrification should therefore take centre stage . As emphasised by experts from the ‘Sustainable Mobility Partnership for All’, data on informal transport systems can play a critical role in planning out efficient and demand-responsive EV public transport systems.

Addressing the question of where EV charging infrastructure and battery-swapping systems need to be built lies at the heart of successful EV network planning. The data WhereIsMyTransport produces on modal split, route distances, vehicle manufacturing brand, passenger capacity, stopping patterns, station points of interest (POIs) and overall coverage of transport systems across emerging-market cities can provide much-needed insights to support EV network planning efforts, of both industry players and governments.

Unfortunately, the reality of the current market is one where the EV transition is being kick-started without a clear view of the transport system as a whole, excluding informal transport operations from planning considerations . Private sector players are competing to install their EV charging stations in the more profitable but already saturated areas of the city, and governments are handing out subsidies to accelerate the installation of charging stations incompatible with the realities of the grid’s capacity. This is particularly problematic for low-income countries, where accessible or reliable electricity supply is still not a given for many households and where EV charging stations are being built without taking into account grid stability. In the majority of African countries, fewer than half of those connected to the grid have reliable electricity.

The necessity to take data-driven decisions on charging infrastructure locations is echoed in a recent publication by the UN Habitat and the Urban Electric Mobility Initiative: “Rolling-out electric mobility requires the deployment of an adequate public charging infrastructure, which is one of the main challenges to the uptake of e-mobility in cities. This requires knowledge of electricity generation capacity, transport demand, land availability and e-mobility uptake projections”.

The UK’s Charge Project demonstrates how efficient and effective implementation of EV charging infrastructure can be planned for when transport data is combined with electric network data. Knowing where, when and how to charge are key questions that need to be answered before electric vehicles are rolled out in mass on the network. Obtaining comprehensive data on transport networks, across both formal and informal modes, should therefore be the first step to embarking on the electromobility transition. With the transport sector accounting for nearly 22% of global energy-related CO2 emissions, of which more than 40% are attributable to urban transport, it is imperative that developing cities are supported in their electro-mobility journey with comprehensive transit and location data.

However, electric two-and-three wheeler startups, informal transport retrofitting pilots and e-bus initiatives cannot be the only answer to the mobility challenges facing developing cities. Phasing out oil-reliant public transportation is needed and investing in electric mobility solutions may well improve the overall picture quite substantially, but there is a far larger challenge that is omitted from these ambitions: addressing the complex operations of informal transport systems that characterise lower-income countries’ urban mobility. Electrifying minibus taxis is not synonymous with more reliable, affordable and convenient public transport, and we need to prioritise the understanding and improvement of overall informal transport systems data first.

How many informal transport operators currently run a route? Which corridors have an oversupply of informal routes? How do formal and informal routes overlap? Which parts of the network could the formal public transport system be reaching where demand is high but unmet? How do fares of informal transport systems compete with formal systems? What effect is this having on public transport demand?

Understanding and rethinking how informal transport systems operate lies at the heart of the public transport decarbonisation agenda for emerging-market cities. Moving forward, informal transport data collection initiatives, such as WhereIsMyTransport, can provide invaluable insights first and foremost on where efficiency gains can be made, and help prioritise electric-mobility initiatives accordingly.

Louise Ribet

Louise Ribet is an urban planner by training and a fellow of the UN SDSN Youth Local Pathways program. She is passionate about making cities more resilient and creating decarbonised transport systems. She is currently the Global Partnerships Lead at WhereIsMyTransport, where she works with multilateral development banks and private sector companies to support the delivery of sustainable urban mobility projects in emerging-market cities

Louise Ribet

Louise Ribet is an urban planner by training and a fellow of the UN SDSN Youth Local Pathways program. She is passionate about making cities more resilient and creating decarbonised transport systems. She is currently the Global Partnerships Lead at WhereIsMyTransport, where she works with multilateral development banks and private sector companies to support the delivery of sustainable urban mobility projects in emerging-market cities