27 November 2023 In Asia, Blog Post

Towards gender equitable urban mobility systems in Asia

By Sonal Shah, Founder, Urban Catalysts and Executive Director, Centre for Sustainable and Equitable Cities

Transport is the fulcrum that can pivot women’s participation in the workforce, enable them to access opportunities and live fuller lives. However, transport systems in Asia are not always gender neutral and often place different burdens on men, women and other gender and sexual minorities.

In 2020, men in the age group of 15-59 years constituted only 33% of the total population in Asia. Women, girls, infants, toddlers, adolescents and the elderly constituted more than two-thirds of the population in Asia.[1] The limited access to and safety of transportation is estimated to be the greatest obstacle to women’s participation in the labour market in developing countries, reducing their participation probability by 16.5%.[2] Meanwhile in Bangladesh, better rural roads led to a 49% increase in male labour supply and a 51% increase in female labour supply.[3]

Gender differences in mobility

Women have lower ownership of and access to personal vehicles than men, making them more dependent on walking, public transport and paratransit. Technology enabled new mobility services (such as ride hailing, carpooling, bike sharing, micro mobility) have provided additional transport options.

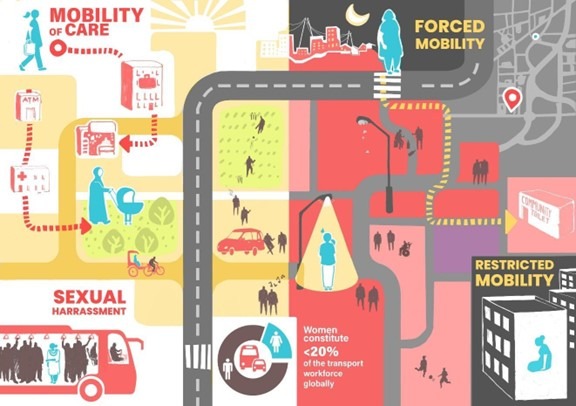

Women’s travel differs from that of men in specific ways (Figure 1), including:

- Mobility of care and trip chaining: Women make shorter trips, with travel characterised by the mobility of care i.e., trips associated with (often unpaid) household and care-related work. Women tend to trip chain, i.e., they combine multiple purposes and destinations in a single journey. These characteristics mean that women may consistently travel during both peak and off-peak hours or travel more in the off-peak hours. Moreover, they frequently travel with dependents- children or the elderly and carry groceries. Women’s travel during off-peak hours of public transport may result in longer waiting times and sometimes necessitate the use of paratransit or other more expensive modes of transport.

- Forced immobility: Unsafe transport, patriarchal socio-cultural norms may restrict women’s mobility and contribute to forced immobility. Restrictions may be placed on travel times, distances, modes in different socio-cultural contexts.

- Forced mobility: Conversely, women may be forced to travel due to the unavailability of facilities. The lack of private sanitation facilities compels women in lower income settlements to use community toilets or peripheries of settlements in rural areas, placing themselves at risk of harassment and violence.

- Women face sexual harassment in public spaces, which can be visual, verbal and physical.

- Gender minorities experience cissexism and may be denied equal treatment, face sexual harassment and violence on public transport by passengers and service providers alike. Transwomen may not be permitted to occupy seats reserved for women, gender minorities may be refused travel or charged more on paratransit.

- The transport sector is male dominated. Women constitute less than 20% of the transport workforce globally. Most women and gender minorities employed in the sector are generally in the capacity of support staff for maintenance of facilities. They are poorly represented in management, leadership, frontline workers in passenger and freight transport and as asset owners.

Statistics in India indicate that women walk more than men for work[1] and are more likely to use paratransit than men. In Pakistan, women are 150% more likely to use paratransit modes like rickshaws and qingqis (motorcycle-rickshaws) than men and when travelling beyond walking distance, they are 30% more likely to use public transport than men[2]. In Shizuoka, Japan most public transport users are female. Their travel patterns were observed to be more diverse in space and time than that of male passengers[3]. In Sri Lanka, women who use ride hailing as their primary mode of transport are 40% more likely to use it than men[4].

Walking and cycling – solutions towards gender responsive mobility systems in Asia

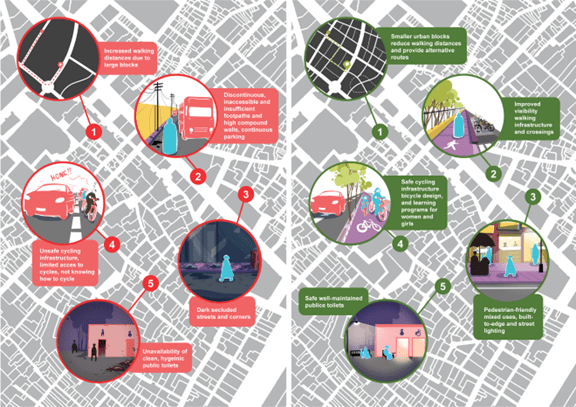

The lack of comfortable, safe and secure infrastructure is a major concern (Figure 2). The overarching and specific gender issues related to walking are i) insufficient, discontinuous and inaccessible pedestrian infrastructure; ii) encroachment by vehicles; iii) no shading; iv) secluded streets; v) blind spots and dark corners which impede visibility; vi) absence of well-maintained and separate toilets; vii) a lack of gender diversity; viii) high vehicle speeds and unsafe pedestrian crossings.

The overarching and specific gender issues related to cycling include the lack of safe cycling infrastructure such as cycling tracks, which provide protection from motor vehicles, continuous surface, street lighting. Additionally, women may not have access to a cycle, know how to cycle and repair it or express greater concerns in cycling alone especially as new users. They may also face harassment while cycling. Public bicycle sharing systems may not consider women’s origin and destinations, shorter travel distances making it more expensive than public transport or paratransit, and the gender gap in digital technology.

How can we achieve gender responsive mobility through walking?

- Improve street network connectivity and reduce travel distances by reducing urban block lengths, preferably between 100-150m.

- Ensure separate and well-maintained toilets with clear signages regarding their location.

- Ensure clear frontage, walking and multi utility zones (MUZ) for footpaths for unobstructed movement of pedestrians.

- Design accessible footpaths with anti-skid surfaces, consistent levels and widths. They must be continuous at property entrances or provided with access ramps not steeper than 1:12 slope.

- Improve perception of safety through well-lit streets and elimination of dark spots by installing and maintaining streetlights.

- Provide shade and thermal comfort through with trees or other shading devices.

- Provide dedicated resting spaces for persons on wheelchairs and seating at regular intervals, which will be beneficial for pregnant women, care givers and the elderly.

- Allocate vending spaces for street vendors in the MUZ for eyes on the street, with dedicated spaces for female vendors, especially female headed households.

- Design suitable interventions for blind spots, dark corners and dead spots. These include porous compound walls that encourage clear sightlines, vertical clearance, street mirrors.

- Surveillance through CCTV cameras and regular police patrolling can be encouraged along deserted stretches; locate police booths at regular intervals with balanced representation of trained female police personnel.

How about cycling?

- Improve women and girls’ access and ownership of bicycles, teach them how to cycle, repair and maintain bicycles.

- Build cycle tracks instead of cycle lanes as they ensure safety through physical separation from the motor vehicles. Where cycle tracks are not feasible, ensure traffic calming with design speeds less than 30kmph.

- Design safe crossings based on pedestrian and cycling access points (preferably not exceeding 150-200m on major roads); create bicycle boxes and paths at intersections.

- Provide dedicated signal phases for pedestrians and cyclists; signal phase timings on major roads should consider lower crossing speeds by pregnant women, elderly, children and care givers.

- Implement campaigns on pedestrian safety, safe cycling; create gender balance in representation in public spaces through legible and gender inclusive signage.

Don’t forget public bicycle sharing systems, which may also be applicable for micro mobility services:

- Provide a dense network of stations: Locate stations in areas that women and girls travel to and near public transport – active places, provide safe access through lighting, CCTV cameras, provide SOS buttons at the stations with a dedicated safety team to address crimes that women and gender minorities face.

- Consider lower registration fees and fares that are sensitive to women’s travel patterns, SMS based renting for non-smartphone users.

- Provide a variety of bicycle designs that include baskets or storage, consider women’s ergonomic comfort.

As Asia continues to urbanize over the next decade, a gender-responsive mobility system can strengthen the right to the city for women, girls and gender minorities by enabling access to employment, education, health facilities and markets. Simultaneously, it can translate to increased use of public transport and improve sustainability of transport projects, enable women’s workforce participation and economic development.

[1] UNFPA 2020

[2] ILO 2017

[3] W. Yunxian and Z. Qun, 2012

[4] Office of the Registar General and Census Commissioner, “Statistics from Population Census 2011 | Labour Commissioner

[5] Fizzah Sajjad et al., “Gender Equity in Transport Planning Improving Women’s Access to Public Transport in Pakistan” (International Growth Center, March 2017), https://www.theigc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Sajadd-et-al-policy-paper-2017_1.pdf.

[6] Shasha Liu et al., “Exploring Travel Pattern Variability of Public Transport Users Through Smart Card Data: Role of Gender and Age,” IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems PP (December 22, 2020): 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2020.3043021.

[7] Alexa Roscoe et al., “Women and Ride-Hailing in Sri Lanka” (Sri Lanka: International Finance Corporation, 2020), https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/REGION__EXT_Content/IFC_External_Corporate_Site/South+Asia/Resources/Women+and+Ride-hailing+in+Sri+Lanka.

Sonal Shah

Sonal Shah is the founder of The Urban Catalysts and the Executive Director of the Centre for Sustainable and Equitable Cities. She is committed to catalyzing climate resilient, equitable cities, transport and public spaces.