8 July 2020 In Blog Post, COVID-19, Dialogue and Networking, Global, Public Transport, Sustainable Development

Post-COVID Recovery: Major challenges for public transport

Sergio Avelleda, Director of Urban Mobility, WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities

The post-pandemic period will test one of the vital elements of our great cities. Public transport systems are facing unprecedented challenges, which will put their viability at risk.

The city’s existence derives from an economic, social and psychological necessity: the desire and need to live together and share. Still, large scale urban growth has increased distances and complicated opportunities for meaningful coexistence. So to keep alive the element which generated cities, simple mobility systems were developed in urban spaces. The increase in the complexity of the urban fabric has also demanded an increase in the complexity of mobility systems – new modes, integrations, user fee challenges, active and motorised mobility, differentiated services, shared modalities, etc.

Besides the parallels between the urban fabric complexity and the urban mobility systems, we can also find parallels between wealth, poverty, and lack of access. In a recent study, published by WRI, the divergences in the accessibility indices in Johannesburg and Mexico City were made apparent. In those cities, we are able to see how access to jobs and opportunities has a completely different profile in high and low-income regions. The low-income population, overall, depends on public transport systems to access work opportunities.

Before the crisis caused by COVID-19, we had already observed difficulties in public transport systems to find new sources of funding that would provide financial relief for quality operations, while at the same time, allow for the investments needed for the expansion and improvement of systems. The lack of financial inputs provoked a decline in service quality contributing to a loss in users and an aggravated financial crisis.

The crisis revealed various circumstances that limit the quality, intelligence and resilience in urban mobility systems: limited sources of funding, low level of governance (especially in metropolitan areas), lack of integration, outdated operator hiring models, urban design that concentrates work opportunities and spreads out housing, among others.

In this article, I’ll focus on one of those elements: the risk of collapse due to the lack of funding sources.

Sources of funding for public transport

The sources of funding for public transport services are, in general, two: the fees paid by users and the subsidies provided by public budgets.

When we charge user fees for public transport, we imply that people are benefiting from the services and, therefore, must pay the related costs. Conversely, when we apply money from the public budget to finance transport systems, we are assuming that these systems provide benefits that go beyond those enjoyed by its users. These benefits are related to the existence of positive externalities which justify the use of resources from the taxpayers as a whole (not necessarily just users of public transport). The main externalities of this kind are the reduction in traffic congestion, emission of pollutants, and road traffic fatalities, as well as an increase in competition and the efficiency of cities.

However, these two sources of funding have not proven to be sufficient, as mentioned previously, to ensure the supply of quality services. This issue generates a reduction in the number of public transport passengers and condemns those who have no other option to a lower condition of accessibility and quality of life.

Therefore, there is an urgent need for the elaboration and implementation of public policies aimed at protecting public transport systems, among them, the guarantee and expansion of funding sources.

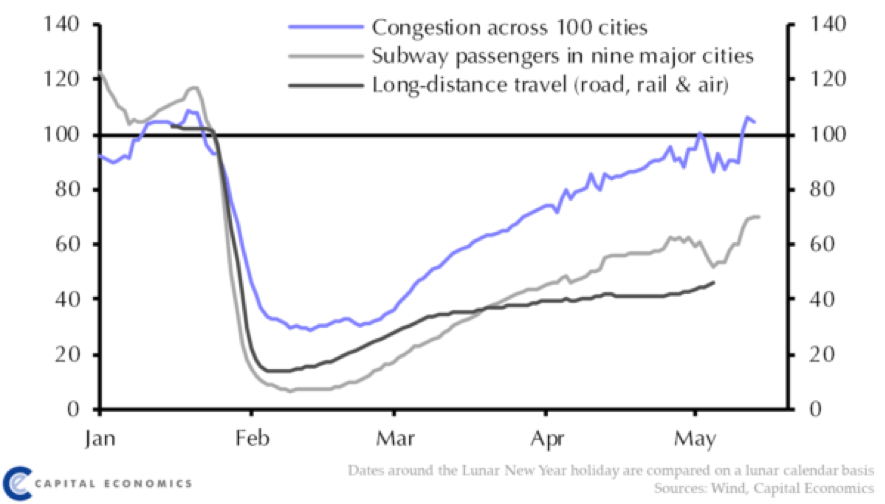

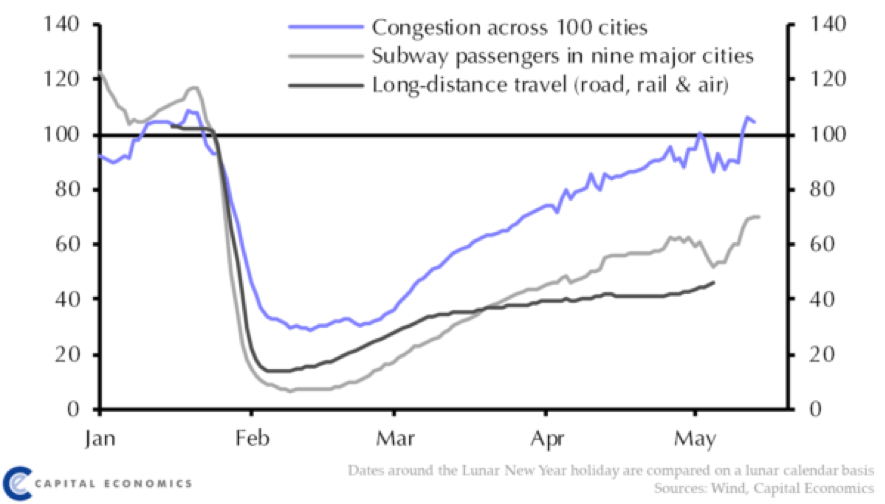

User fee revenues have decreased in the post-COVID period. Chinese cities that have already ended social isolation measures show us that the number of passengers transported are fewer than before the pandemic.

One of the reasons for these numbers is the fear of infection, followed by reduction in economic activity and an uptick in work from home patterns.

The passenger reduction will force an adaptation of the service offer, which may consequently reduce part of some variable and fixed costs. Nevertheless, there will be a reduction in scale that may determine the increase in the cost per passenger transported, generating even greater deficits.

These deficits will elevate the pressure over the public budget for the adoption or the extension of subsidies. The issue is that those budgets will be pressured by many other demands: public health, loss of revenue due to the economic crisis, housing challenges, and programs to stimulate the economy, among others.

Public transport is an essential service and cannot rely only on fees and public resources. In order to avoid its collapse, it is mandatory to find other sources of funding.

The use of individual motorised transport generates negative externalities. The person who decides to move by car enjoys the benefits of comfort and privacy, but on the other hand, causes harmful effects like: energy inefficiency (more than one ton to move 75kg, on average), high occupancy of public space, traffic jams, pollution, risk of fatalities, etc. When we decide to move by public transport, we are transcending the benefits far beyond our own surroundings. The whole society benefits from our decision.

Consequently, there is a cost burden borne by the society when someone decides to move by individual motorised transport.

It’s quite apparent to conclude that it’s time for cities to consider the implementation of a new source of funding for public transport and also the creation of charges over the use of private vehicles, as well as allocating these resources to finance the operation and invest in the public transport systems.

Some cities have already taken this step: London and New York are well-known examples. New York, like London before it, has recently approved, after years of discussion, the implementation of congestion pricing to access Manhattan.

In my experience as a public administrator, I’ve seen many politicians avoid this discussion due to a fear in how their voters, as well as users of private vehicles, would react. Automobiles are still seen as a symbol of freedom that feeds the fear of adopting any measure that would restrict its use.

However, in my opinion, the society’s negative reaction to the adoption of financing models for public transport based on the use of individual motorised transport is due to lack of information on a key point.

How much does society pay for the use of private vehicles?

In general, when we look at public budgets in cities or states, there is usually a budget line which is a subsidy for public transport.

Since 2005, São Paulo has been paying a subsidy to supplement the amount collected by the user fees. The subsidy guarantees a tariff integration, which has increased significantly the utility and use of buses and trains.

In São Paulo, people know the size of the subsidy that is paid and society can discuss these values to decide if they are more pressing than other expenses that the government must bear.

Nevertheless, there isn’t an item in public budgets named ‘subsidy to individual motorised transport’. Therefore, the absence of this line creates the false feeling that the use of private motorised transport doesn’t cost anything to the public.

We can enumerate several expenditures to the public sector: thousands of kilometers of asphalt that have to be maintained, engineering and signaling systems which need to run 24/7, large sums of money spent on congestion, public health issues due to accidents on the roads or respiratory diseases caused by pollution, not to mention the payment of social security to compensate family members of the dead, wounded, or disabled.

These expenses are scattered or hidden in other budget lines instead of being included in a ‘subsidy to individual motorized transport’. As there is no consolidation of the number, this remains hidden, preventing the debate about whether it is too much or too little, or even if it is fair or not for the taxpayer who does not use a private vehicle to continue subsidising its use.

This way, it will be natural to discuss whether or not taxpayers should support these values without any consideration from the user of individual transport (why do we demand compensation from the public transport user and not the automobile owner?).

Through efforts such as this, it will be much easier to convince society of how correct it is, under the perspective of economic theory, to establish the charge for individual motorised transport in favour of financing public transport.

Sergio Avelleda

Sergio Avelleda, Director of Urban Mobility, WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities

The post-pandemic period will test one of the vital elements of our great cities. Public transport systems are facing unprecedented challenges, which will put their viability at risk.

The city’s existence derives from an economic, social and psychological necessity: the desire and need to live together and share. Still, large scale urban growth has increased distances and complicated opportunities for meaningful coexistence. So to keep alive the element which generated cities, simple mobility systems were developed in urban spaces. The increase in the complexity of the urban fabric has also demanded an increase in the complexity of mobility systems – new modes, integrations, user fee challenges, active and motorised mobility, differentiated services, shared modalities, etc.

Besides the parallels between the urban fabric complexity and the urban mobility systems, we can also find parallels between wealth, poverty, and lack of access. In a recent study, published by WRI, the divergences in the accessibility indices in Johannesburg and Mexico City were made apparent. In those cities, we are able to see how access to jobs and opportunities has a completely different profile in high and low-income regions. The low-income population, overall, depends on public transport systems to access work opportunities.

Before the crisis caused by COVID-19, we had already observed difficulties in public transport systems to find new sources of funding that would provide financial relief for quality operations, while at the same time, allow for the investments needed for the expansion and improvement of systems. The lack of financial inputs provoked a decline in service quality contributing to a loss in users and an aggravated financial crisis.

The crisis revealed various circumstances that limit the quality, intelligence and resilience in urban mobility systems: limited sources of funding, low level of governance (especially in metropolitan areas), lack of integration, outdated operator hiring models, urban design that concentrates work opportunities and spreads out housing, among others.

In this article, I’ll focus on one of those elements: the risk of collapse due to the lack of funding sources.

Sources of funding for public transport

The sources of funding for public transport services are, in general, two: the fees paid by users and the subsidies provided by public budgets.

However, these two sources of funding have not proven to be sufficient, as mentioned previously, to ensure the supply of quality services. This issue generates a reduction in the number of public transport passengers and condemns those who have no other option to a lower condition of accessibility and quality of life.

Therefore, there is an urgent need for the elaboration and implementation of public policies aimed at protecting public transport systems, among them, the guarantee and expansion of funding sources.

User fee revenues have decreased in the post-COVID period. Chinese cities that have already ended social isolation measures show us that the number of passengers transported are fewer than before the pandemic.

When we charge user fees for public transport, we imply that people are benefiting from the services and, therefore, must pay the related costs. Conversely, when we apply money from the public budget to finance transport systems, we are assuming that these systems provide benefits that go beyond those enjoyed by its users. These benefits are related to the existence of positive externalities which justify the use of resources from the taxpayers as a whole (not necessarily just users of public transport). The main externalities of this kind are the reduction in traffic congestion, emission of pollutants, and road traffic fatalities, as well as an increase in competition and the efficiency of cities.

However, these two sources of funding have not proven to be sufficient, as mentioned previously, to ensure the supply of quality services. This issue generates a reduction in the number of public transport passengers and condemns those who have no other option to a lower condition of accessibility and quality of life.

Therefore, there is an urgent need for the elaboration and implementation of public policies aimed at protecting public transport systems, among them, the guarantee and expansion of funding sources.

User fee revenues have decreased in the post-COVID period. Chinese cities that have already ended social isolation measures show us that the number of passengers transported are fewer than before the pandemic.

One of the reasons for these numbers is the fear of infection, followed by reduction in economic activity and an uptick in work from home patterns.

The passenger reduction will force an adaptation of the service offer, which may consequently reduce part of some variable and fixed costs. Nevertheless, there will be a reduction in scale that may determine the increase in the cost per passenger transported, generating even greater deficits.

These deficits will elevate the pressure over the public budget for the adoption or the extension of subsidies. The issue is that those budgets will be pressured by many other demands: public health, loss of revenue due to the economic crisis, housing challenges, and programs to stimulate the economy, among others.

Public transport is an essential service and cannot rely only on fees and public resources. In order to avoid its collapse, it is mandatory to find other sources of funding.

The use of individual motorised transport generates negative externalities. The person who decides to move by car enjoys the benefits of comfort and privacy, but on the other hand, causes harmful effects like: energy inefficiency (more than one ton to move 75kg, on average), high occupancy of public space, traffic jams, pollution, risk of fatalities, etc. When we decide to move by public transport, we are transcending the benefits far beyond our own surroundings. The whole society benefits from our decision.

Consequently, there is a cost burden borne by the society when someone decides to move by individual motorised transport.

It’s quite apparent to conclude that it’s time for cities to consider the implementation of a new source of funding for public transport and also the creation of charges over the use of private vehicles, as well as allocating these resources to finance the operation and invest in the public transport systems.

Some cities have already taken this step: London and New York are well-known examples. New York, like London before it, has recently approved, after years of discussion, the implementation of congestion pricing to access Manhattan.

In my experience as a public administrator, I’ve seen many politicians avoid this discussion due to a fear in how their voters, as well as users of private vehicles, would react. Automobiles are still seen as a symbol of freedom that feeds the fear of adopting any measure that would restrict its use.

However, in my opinion, the society’s negative reaction to the adoption of financing models for public transport based on the use of individual motorised transport is due to lack of information on a key point.

How much does society pay for the use of private vehicles?

In general, when we look at public budgets in cities or states, there is usually a budget line which is a subsidy for public transport.

Since 2005, São Paulo has been paying a subsidy to supplement the amount collected by the user fees. The subsidy guarantees a tariff integration, which has increased significantly the utility and use of buses and trains.

In São Paulo, people know the size of the subsidy that is paid and society can discuss these values to decide if they are more pressing than other expenses that the government must bear.

Nevertheless, there isn’t an item in public budgets named ‘subsidy to individual motorised transport’. Therefore, the absence of this line creates the false feeling that the use of private motorised transport doesn’t cost anything to the public.

We can enumerate several expenditures to the public sector: thousands of kilometers of asphalt that have to be maintained, engineering and signaling systems which need to run 24/7, large sums of money spent on congestion, public health issues due to accidents on the roads or respiratory diseases caused by pollution, not to mention the payment of social security to compensate family members of the dead, wounded, or disabled.

These expenses are scattered or hidden in other budget lines instead of being included in a ‘subsidy to individual motorized transport’. As there is no consolidation of the number, this remains hidden, preventing the debate about whether it is too much or too little, or even if it is fair or not for the taxpayer who does not use a private vehicle to continue subsidising its use.

This way, it will be natural to discuss whether or not taxpayers should support these values without any consideration from the user of individual transport (why do we demand compensation from the public transport user and not the automobile owner?).

Through efforts such as this, it will be much easier to convince society of how correct it is, under the perspective of economic theory, to establish the charge for individual motorised transport in favour of financing public transport.