Two Years In — How Are the World's Multilateral Development Banks Doing in Delivering on their $175 Billion Pledge for More Sustainable Transport?

By Michael Replogle and Cornie Huizenga

Michael Replogle, Managing Director for Policy and Founder, Institute for Transportation and Development Policy, and Cornie Huizenga, Secretary General of the Partnership on Sustainable Low Carbon Transport, both serve as observers to the Technical Working Group of MDB Working Group on Sustainable Transport

In June 2012 the eight largest multilateral development banks (MDBs) made a voluntary commitment to invest $175 billion over the coming decade for more sustainable transportation, with annual reporting using a common monitoring and reporting framework. This was one of the good news stories coming out of the Rio+20 Conference on Sustainable Development.

The pledge has led to unprecedented collaboration across a single sector by the MDBs, with the establishment of the MDB Working Group on Sustainable Transport. Further cooperation has been developed through a subordinate Technical Working Group. The latter has two external observers– including the author — from the Partnership on Sustainable Low Carbon Transport (SLoCaT), a partnership that includes MDBs, UN agencies, non-governmental organizations, and various trade associations.

The first MDB report related to this pledge, published in February 2014, created a baseline. The issuance in February 2015 of the Progress Report (2013–2014) of the MDB Working Group on Sustainable Transport, is a good opportunity to take stock.

How much progress has been made?

The MDBs are clearly on track to lend more than their target rate of $17.5 billion per year for transport. In 2012 the banks lent $20 billion on transport; in 2013 they lent about $25 billion.

But have the MDBs made progress towards greater sustainability in these investments? What might be done to speed action?

While there are signs of progress at many MDBs, the latest report is more dominated by anecdotes than consistent measurable indicators. Only four of the eight MDBs sought to report on the sustainability of their entire transport lending portfolio. One additional MDB reported on a subset of its portfolio.

As a share of project approvals, lending for roads continues to dominate, constituting 58% of projects approved in 2013 across all 8 MDBs. Urban transport (20%) and rail transport (12%) projects are a growing area for many of the banks, but the lack of good baseline data from 2012 makes it hard to say from the report whether there is any trend across all the banks.

Not all road projects are unsustainable, and not all urban and rail transport projects are sustainable. That is a key reason why it is important for the banks to employ a common framework to evaluate and report on how each project contributes to social, economic, and environmental sustainability indicators or criteria, as well as to risks to sustainability, and to show how projects of each type are made more sustainable over time. The MDBs have agreed to such a general conceptual framework, but institutional differences remain over how to harmonize annual evaluation and reporting.

The Asian Development Bank has developed a Sustainable Transport Appraisal Rating (STAR) tool that can be used quickly with low cost and burden to perform such evaluations. ADB has applied STAR to all 46 ADB transport projects approved for funding in 2012-2013, as well as to select initiatives in project preparation, where it has shown promise in helping project officers identify how to improve sustainability. ITDP has been assisting ADB in 2014-15 to help develop a user-friendly expert system and knowledge management software application organized around STAR.

Five other MDBs – the African Development Bank, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Islamic Development Bank, Corporación Andina de Fomento, and the Inter American Development Bank — have begun pilot testing a modified STAR framework to evaluate their projects.

Two other MDBs use different methods to evaluate project sustainability. The European Investment Bank (EIB) uses its multisectoral3 Pillar and Results Measurement (ReM) Frameworks; the World Bank uses an undisclosed internal methodology. The MDBs state their “hope to be in a position to monitor and report on the sustainability of all our new projects under a joint framework” by the end of 2015. That is good news.

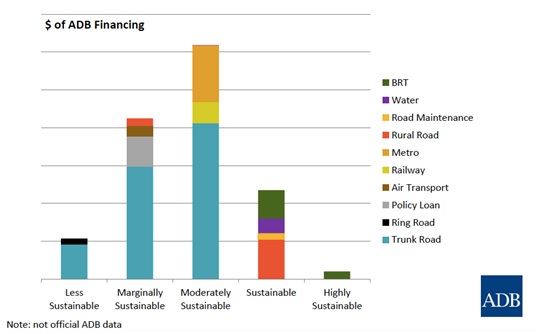

ADB’s pilot testing of the STAR tool to date shows how a common evaluation framework could be used to measure progress year-to-year and across institutions. It also reveals how different project types may vary in their overall sustainability rating, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Asian Development Bank Sustainability Rating by Subsector (Source: ADB STAR Transport Forum 2014)

Urban ring roads score low on across all dimensions of sustainability; trunk roads may range from low to moderately sustainable; rural road projects tend to score higher, with strong social and economic benefits. Bus Rapid Transit (BRT), water, and road maintenance projects also score high. Metro and rail projects tend to fall in the moderately sustainable to sustainable categories. Air transport tends to fall in the marginally sustainable category.

For most projects there are multiple interventions in project design and concept that could improve the project sustainability in one or more dimensions. A road project could be designed for improved traffic safety or bundled together with an initiative to spur development of new or more efficient freight or passenger transport services. A rail project could be coupled with an effort to modernize locomotives to reduce air pollution and to improve logistics for intermodal services.

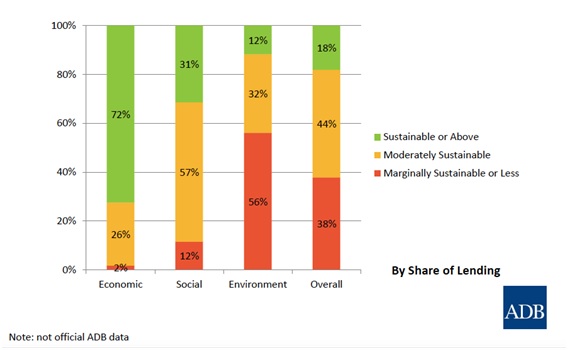

ADB’s application of STAR to its projects also suggests, as shown in Figure 2, that environmental sustainability is the area where most improvement is needed to boost the sustainability of transport lending. Only 12 percent of rated projects scored sustainable or above for the environmental dimension. MDBs have traditionally focused on economic sustainability: 72 percent of ADB’s scored projects rated sustainable or above on this dimension. Various safeguard policies and a growing focus on poverty alleviation under the Millennium Development Goals has tended to boost social sustainability. Of ADB’s scored projects, 31 percent of rated sustainable or above on this dimension.

Figure 2: ADB Sub-Ratings by Objective for Transport Projects Approved in 2012-2013 (Source: ADB STAR Transport Forum 2014)

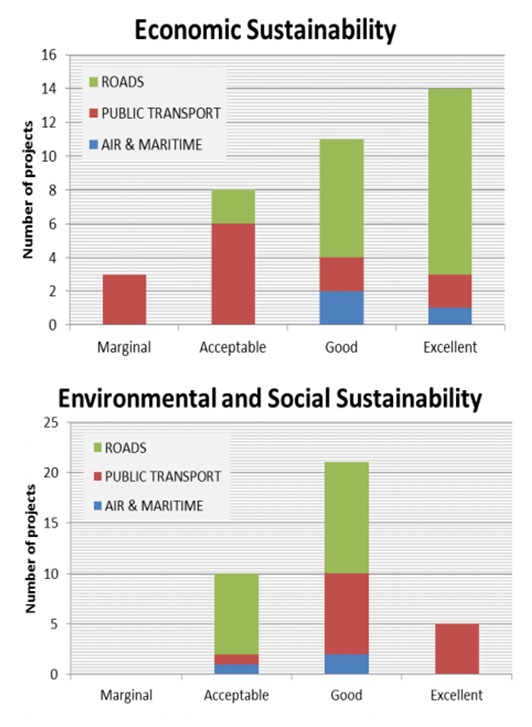

The EIB’s analysis shows a similar result – that road projects tend to score well for economic sustainability but not as well for environmental and social sustainability. Public transport projects tend to rate lower on their economic sustainability and much higher on social and environmental criteria. A shift in portfolio composition together with greater efforts to enhance the sustainability elements in individual projects of any type is warranted to boost overall portfolio sustainability.

Figure 3: EIB 2013 Transport Projects (Source: Progress Report (2013–2014) of the MDB Working Group on Sustainable Transport)

MDBs face challenges redirecting their lending to more sustainable types of transport over the 10 year commitment period. Their loans are provided in response to requests from developing country governments, so the governments need to be convinced to make changes in both the types of investments in their MDB lending pipelines and the way that individual investments are formulated. One issue is how long it takes to change. Future lending pipelines generally earmark future lending for several years ahead, allowing time for the many tasks of project preparation to be carried out. Governments generally don’t like to abandon projects already in the pipeline, particularly when project preparation is underway. Consequently, it is less likely we will see dramatic changes in transport lending pipelines during the first few years after the 2012 commitment, except perhaps in the small number of countries that have adopted more aggressive policies for shifting to more sustainable types of transport. A further challenge concerns inertia in the process of programming future MDB lending projects. In many countries, the pattern of transport lending has been similar for decades, with priority going to national highways, and less lending going to more sustainable types of transport, some of which falls under the purview of sub national authorities. It is therefore imperative that MDBs energize their dialogue with governments to persuade them of the need to redirect future lending to more sustainable types of transport and widen the group of transport agencies they work with to prepare project proposals for including in future lending pipelines.

For the MDBs’Rio+20 voluntary commitment to be effective and their reporting of sustainability to be taken seriously, timely progress is needed in several areas.

The MDB Working Group on Sustainable Transport should:

- Ensure that each MDB uses STAR or a modified version of STAR for sustainability rating, with disclosure of the detailed methodologies used by each MDB;

- standardize nomenclature of classifications across the rating systems;

- seek to harmonize underlying criteria and methods as much as possible between the MDBs so that similar projects will be rated using similar factors and thresholds for performance, with similar results;

- make explicit where differences exist between rating systems used in the annual MDB reporting process; and

- using common definitions and methods, report on a standard set of other indicators, such as the number, extent, and value of lending by project and activity type, and on anticipated project impacts, such as anticipated direct and indirect greenhouse gas emissions, relative to a do-nothing scenario.

Each MDB should:

- develop a verification or peer review process to ensure integrity of the sustainability ratings for projects;

- once robust sustainability rating systems have been established, use these not only to evaluate projects after board approval, but also during project preparation and project pipeline development, where there are also significant opportunities to improve sustainability;

- give some weight in management performance evaluation to steps that staff take to increase the overall sustainability of transport lending over time; and

- incorporate sustainability rating into training programs and professional development for project officers, safeguards staff, agency staff in member developing countries, and consultants involved in project preparation.

Sustainability rating of transportation projects might eventually be turned into a new safeguard, with mandatory reporting for each project. However, that will take some time. An intermediate step would be for the boards or senior management of MDBs to require all transport projects to be rated using a tool like STAR early in the project development cycle, and require staff to use the rating process as an internal expert system and knowledge management framework to help improve the quality of projects at all stages of consideration by MDBs and their clients.

Governments and NGOs should also encourage transport agencies, national development banks, and financial intermediaries to pilot test tools like STAR to help influence a broader array of transport investments. After all, spending on transport by national and sub-national governments and the private sector exceeds MDB lending 30-fold. While MDB lending often opens the door for larger investments in projects, how sustainable the world’s transportation systems will be in 2030 will depend on more than shifting MDB lending alone.

MDBs face many challenges to do more with less and to do so in competition with new development banks that may lend with fewer safeguards. This makes it all the more imperative that MDBs show leadership, focusing their investments in ways that accelerate the transition to a more sustainable development path. That is the real promise of the Rio+20 MDB voluntary commitment, which remains a laudable achievement and has positively shifted the nature of MDB-NGO engagement around transportation issues.

Two years into that 10 year pledge, progress is evident, though it remains slow. As the world’s governments adopt new UN agreements on sustainable development goals in September 2015 and on climate change in December 2015, a growing number of stakeholders related to those agreements will be watching for signs that the voluntary commitments in support of sustainable development and climate change are on track to deliver. In the case of the MDBs’ commitment, there is much to be positive about but stakeholders should demand that MDBs keep shifting their lending in to more sustainable types of transport and ask them to speed up their efforts to establish reliable, harmonized and transparent approaches to sustainability rating and reporting.